https://africacenter.org/publication/geostrategic-dimensions-libya-civil-war/

Tarek Megerisi

Libya’s civil war has become an increasingly competitive geostrategic struggle. A UN-brokered settlement supported by non-aligned states is the most viable means for a stable de-escalation, enabling Libya to regain its sovereignty.

HIGHLIGHTS

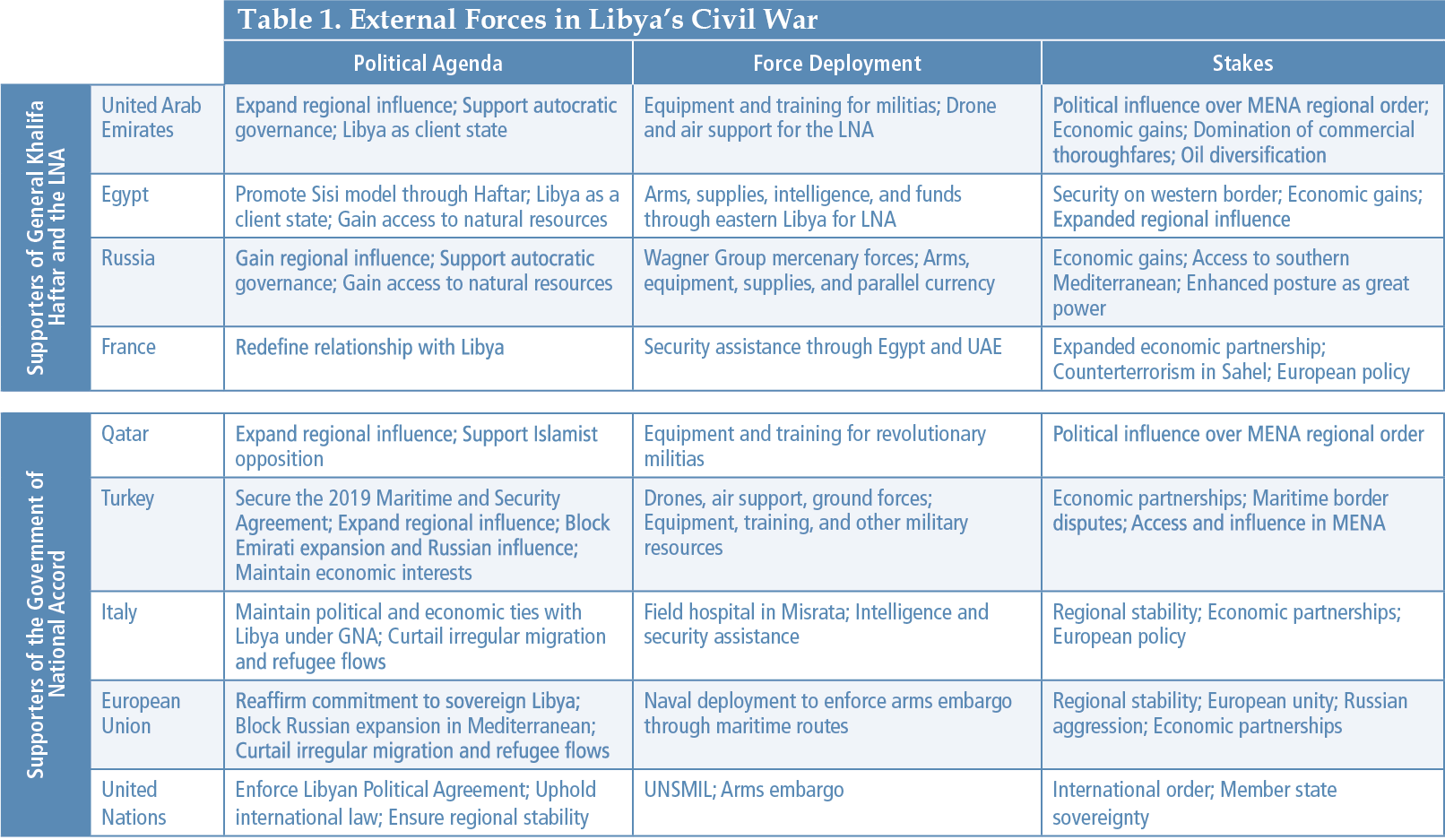

- The Libya conflict has escalated into an increasingly dangerous geostrategic competition for influence, pitting the UAE, Egypt, and Russia against Qatar, most of Europe, and Turkey in a petroleum-rich country straddling the regions of North Africa, southern Europe, the Sahel, and the Middle East.

- General Khalifa Haftar lacks a strong domestic constituency and instead serves largely as a proxy for external actor interests. He has, moreover, consistently acted as an obstacle to de-escalation and stabilization. Consequently, he lacks the standing to be treated as a political equal to the UN-backed government.

- A UN-brokered settlement supported by nonaligned states is the only viable means for a stable de-escalation that would generate a nonthreatening outcome for the regional competitors while enabling Libya to regain its sovereignty.

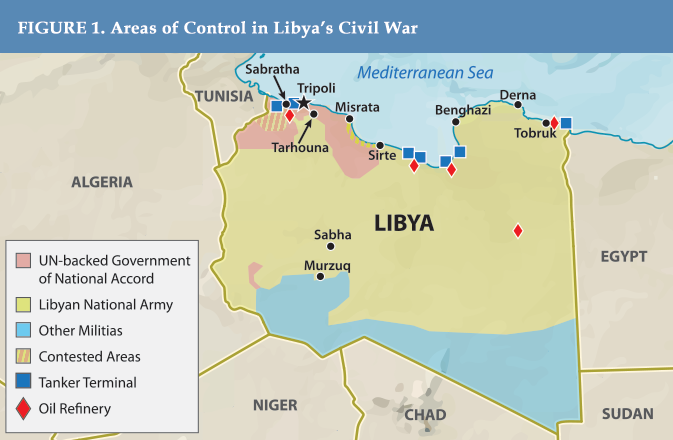

Conflict in Libya has claimed the lives of tens of thousands, generated instability throughout North Africa and the Sahel, and become an increasingly pitched focal point for geostrategic competition. Since April 2019, the civil war in Libya has intensified particularly in the west of the country, where General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA) laid siege to Tripoli in a bid to oust the United Nations-supported Government of National Accord (GNA). The United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) estimates some 231,000 civilians are in the immediate frontline areas, with an additional 380,000 living in areas directly affected by conflict. More than 370,000 people are estimated to remain internally displaced by the violence and hundreds of civilians have been killed since Haftar’s April 2019 assault.

1

According to UNSMIL, the LNA and affiliated forces conducted at least 850 precision air strikes by drones and another 170 by fighter-bombers between April 2019 and January 2020.

2 Of these, some 60 precision air strikes were conducted reportedly by Egyptian and Emirati fighter aircraft. Meanwhile, the GNA and affiliated forces conducted roughly 250 air strikes.

The economic impact of the conflict coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic may cause the country’s GDP to contract by more than 12 percent in 2020. The LNA’s blockade of oil terminals since January 2020 has further deepened the economic crisis. Oil production has plunged to around 120,000 barrels per day from 1.14 million in December 2019. This has resulted in financial losses of approximately $2 billion per month for the state-owned enterprise.

3

While the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, and Egypt have been supporting competing sides of the Libyan conflict from its early stages, the geostrategic stakes escalated in September 2019 with the deployment of Russian mercenaries in support of Haftar’s forces. This precipitated an intervention of Turkish ground forces in support of the GNA. In addition, external actors have deployed Syrian, Chadian, and Sudanese mercenaries, drones, ground-to-air defense systems, and other high-tech assets in an attempt to swing the balance in favor of their proxies.

Note: Areas of control are illustrative and not to be interpreted as precise or constant delineations. (Click image for shareable version.)

Libya’s post-revolutionary decline toward fragmentation and state collapse represents a growing cause for alarm. With external actors coalescing around the two main Libyan factions, the conflict has become increasingly internationalized. This has compounded its complexity, taking on drivers far different from those with which it began. The internationalization of the conflict poses a geostrategic nightmare for the UN’s efforts toward stabilization and has upped the stakes for Libya’s civil war, posing an even greater threat to international security.

4

Drawing Battle Lines

The internationalization of Libya’s transition began with what itself was a very internationalized revolution. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO’s) 2011 intervention, which largely took place from the skies, received most of the attention during Libya’s moment in the Arab Spring. Less recognized, however, were the rival interventions by Qatar and the UAE to equip, train, and otherwise assist Libyan revolutionary militias on the ground, which set the scene for a competition that would come to define Libya’s revolutionary aftermath.

The two Gulf States mobilized their assistance through proxies with whom they had pre-existing relationships and who came to represent their divergent interests. Those who fell into Qatar’s camp included Libyan actors who were ideologically opposed to Muammar el Qaddafi as a tyrant, those who had often been imprisoned or persecuted by him, and those who defined their opposition in Islamist ideology. The UAE maintained links with a technocratic class who had often worked with Qaddafi’s son in a failed reform attempt and with older generations of opposition.

During the revolutionary war, these two distinct camps were often demarcated by personal contacts with a particular militia leader, a go-between from the older generation, or ties to a geographical area. As the war progressed, their military operations, diplomatic dealings, and the machinations of their political proxies who pursued exclusive control over Libya’s levers of power pitted the two camps against each another. The rift grew in acrimony even as the war ended and as the country’s first elections in over half a century took place in July 2012 to elect a parliament, the General National Congress (GNC). This would become the first theatre of this new, now more political, conflict.

Soldiers allied to the internationally-backed Government of National Accord returning from the front lines in Tripoli, April 2019. (Photo:

VOA/H. Murdock)

The two coalitions continued to confront each other rather than compromise in a zero-sum pursuit of wealth and authority encouraged by their backers. The National Forces Alliance (NFA), a political coalition with close ties to the UAE, won a majority and was able to command 64 seats of the GNC (including nominally aligned members of parliament). The Justice and Construction Party (JCP), Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood-aligned political party, counted 34 seats. The myopic use of militias by domestic political actors to achieve their internal political outcomes institutionalized violence as a political tool. Meanwhile, competition over often corrupt business dealings with international partners destroyed the integrity and legitimacy of the GNC as an institution. Once the NFA, plagued by internal fissures and consistently outmaneuvered, failed to make its initial majority count, the coalition boycotted the GNC, severely undermining its effectiveness.

Although the UN hoped that a fresh round of elections could restart a political transition that had been lost to the greed and immaturity of Libya’s political class, the damage was done. Libya’s foreign and domestic factions had fossilized, the use of violence had normalized, and a zero-sum mindset had become locked-in.

Libya’s Geostrategic Significance

If the Arab Spring was a time of regional flux for the Middle East and North Africa, to those in the Gulf with a more stable perch and considerable resources, it was a time of opportunity. As the old pillars of the region collapsed— first Iraq, then Syria, and then Egypt—there was a sense that the moment was ripe for a new regional order. Qatar took the view, perhaps born of its own history of palac e coups, that revolutions birthed new orders and new elites, and thus fully supported revolutionary actors in the hopes that this would create a regional network of friendly, if not gracious, states. Their own role in hosting many of the region’s exiled Islamist dissidents, and the fact that most organized long-standing opposition movements in the region were themselves Islamist, meant that their regional enterprises had a distinctly Islamist flavor.

If Qatar’s approach was built on opportunism and the prospects of soft power, then the UAE’s was forged from fear and realpolitik. The harsh domestic crackdowns on activists and those offering even modest proposals for reform showed an undercurrent of fear in Abu Dhabi that the Arab Spring contagion might cross Emirati borders. Its regional strategy since then shows an Emirati preference for evolution over revolution with a focus on securing key interests. This preference for recreating the old order with new leaders is evident in the UAE’s support for General Abdul Fattah el Sisi in Egypt, the jewel of this policy. Emirati activities in Yemen showcase the economic angle of its policy, an oil diversification strategy to become the regional leader in shipping and logistics, all while maintaining a dominant presence in the network of ports connecting the Far East to the Atlantic.

Libya’s strategic location at the heart of the Mediterranean, the Maghreb, and as a door to sub-Saharan Africa, as well as its significant oil and gas reserves and its revolutionary upheaval, meant that it fell neatly at the intersection of Emirati ideological and economic policies.

5 As the remnants of the state crumbled and Libya destabilized, it attracted others like Egypt and France who saw an opportunity to build a friendly state that could be useful for their own economic, security, and regional policymaking interests.

6 This dynamic continued as Libya’s decline persisted and worsened.

The Haftar Project

“Moving away from politicians employing militias toward a paradigm whereby militias employed politicians.”

The collapse of the GNC was a turning point in Libya’s transition, symbolized best by the re-emergence of Qaddafi-era General Khalifa Haftar who had failed to establish himself after Qaddafi’s ouster. In 2011, he was quickly sidelined and ostracized. Many Libyans were unwilling to work with him, deeming him responsible for atrocities committed during the Chadian war of the 1980s. Others saw him as a divisive force given that they already had a commander, Abdul Fatah Younis. Haftar’s next emergence, a coup-by-television on Valentine’s Day 2014, was laughed off by many at the time. However, it represented the beginning of politics by other means in Libya—the moving away from politicians employing militias toward a paradigm whereby militias employed politicians to provide a shroud of legitimacy.

Although Haftar has often leveraged local Libyan grievances, such as the rise of jihadism in eastern Libya or a long-standing oil blockade by rogue militias, his attempt to grow his position and attract supporters has never been an entirely Libyan or autonomous enterprise. Haftar’s reintroduction to Libya passed through Cairo, where his vision of emulating Qaddafi’s quasi-military dictatorship found resonance with a resurgent Egyptian military institution emboldened by the successful installation of Sisi following Egypt’s aborted democratic transition.

While Haftar’s coup attempt failed to gain traction in Tripoli, he quickly discovered a new raison d’être over the course of 2014—by launching a war on terror in eastern Libya.

7 This allowed him to remain close to Egypt, which supplied him militarily to construct a hybrid security institution that patched together former regime intelligence and military officers with tribal militias and other auxiliary forces such as Salafists. This movement came to represent one side of the growing national divide as some sympathetic and recently elected politicians from the new parliament, the House of Representatives, ordained Haftar and his forces as Libya’s national armed forces. These same politicians had unilaterally moved this new legislative body to Tobruk in eastern Libya in an attempt to side-step their opponents and dominate the parliament, effectively bifurcating governance of the country.

Although the UN attempted to build a new power-sharing institution, the Government of National Accord (GNA), Haftar’s backers lost interest in political compromise in 2015. Under the cover of the war on terror narrative, the UAE built an airbase near Haftar’s headquarters in eastern Libya while the French deployed special forces and provided other expert assistance. Coming at a time when France was increasing its counterterrorism activity to Libya’s south in the Sahel, Haftar’s counterterrorism narrative and Emirati support (with whom France already enjoyed a close security partnership) made him a natural ally. Moreover, Haftar and his wider movement was considered a useful vehicle to expand French influence in Libya, which had long been dominated by Italy, and a key component of the wider security architecture the French were building in the Sahel.

With his external support in place, Haftar refused to support the Libyan Political Agreement, which was intended to reunify the country, and ultimately declared the agreement void in 2017.

8 Haftar himself spent much of this time refusing to meet with any UN or diplomatic missions that were not coming to offer support, as he built up his base in eastern Libya.

9 As the war on terror gradually ended, his foreign backers provided him the technology, finances, airpower, and manpower needed to extend his network further to acquire Libya’s oil export terminals and to conquer the remainder of eastern Libya. All the while, they ensured that no international criticism could come his way for a growing litany of war crimes committed by LNA forces including besieging the city of Derna, the execution-style killings of captured fighters from the Shura Council of Benghazi Revolutionaries, and at least 7 other incidents involving orders from a LNA commander to kill at least 33 prisoners in the area around Benghazi.

10

The Sacrificial Sarraj

The UN talks which birthed the GNA in December 2015 began as a process firmly backed by a host of countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy, in the hopes that it could end Libya’s civil war and create a credible partner for combatting terrorism and migration. However, as the talks dragged on, the crisis worsened, and with hundreds of thousands crossing the Mediterranean and the Islamic State having taken the city of Sirte a year earlier, these needs became more acute. The Libyan Political Agreement which resulted from the UN talks held little local legitimacy and exhibited minimal structural capability to enforce many of its provisions, such as those to secure the capital. Moreover, the new Prime Minister, Fayez al Sarraj, a relatively unknown politician with no clear constituency, was chosen by virtue of being the least controversial and thereby most agreeable person to be found.

Sarraj and his weak government were delivered to Tripoli in March 2016 on an Italian naval vessel. The GNA struggled to operate in a city controlled by militias that were more than happy to hold the GNA hostage as a means of tapping the country’s central bank. Unable to immediately contribute to the counterterror or counter-migration efforts, many international actors who had supported the UN and the GNA quickly abandoned it for more expedient policies. These policies often revolved around nonstate actors and further undermined the GNA, reducing it to the status of a payer rather than a player.

The GNA’s lack of political power was on full display when French President Emmanuel Macron hosted a conference between Haftar and Sarraj in 2018.

11 Dubbed a peace conference, despite the two parties never actually having been at war with each another, it created a false equivalence between the civilian leader of the country and the commander of one of the country’s multitude of armed groups. It also set in play a dynamic that molded Libya’s political process over the coming years, with Sarraj being forced to negotiate deals with Haftar who continued expanding his presence and military power. Meanwhile, even the GNA’s staunchest allies, such as Italy, who had considered Sarraj key to preserving their influence in the country, began to lose confidence.

UN Special Representative Ghassan Salamé tried to break this mold during 2018-2019 to create a new, inclusive political process that would lead to a new civilian government and national security institutions more reflective of Libya’s patchwork of political and military actors. Following a power-sharing agreement struck between Haftar and Sarraj in Abu Dhabi at the end of February 2019, the new UN plan seemed to offer some hope. However, the plan remained highly contested with many in Libya refusing to support it, which eroded UN and international credibility in the country. On March 27, 2019, in a reported meeting between Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Haftar, and Emirati representatives, the decision was made that Haftar would try to seize power by launching a surprise attack on Tripoli—even as UN Secretary General António Guterres was in town trying to salvage the UN-backed political process.

Tripoli or Bust

Haftar’s plan to blitzkrieg Tripoli and assume power in April 2019 failed. He quickly found himself in a war of attrition confronted by the greatest mobilization of fighters Libya had witnessed since the 2011 revolution against Qaddafi.

12 He simultaneously struggled to maintain long supply lines through territory that he controlled only nominally. However, the decision to take Tripoli left Haftar and his backers with few alternatives but to persist or risk losing everything. The finality of the situation, whereby either Haftar wins and sets up a new dictatorship or he loses and a new chapter of Libya’s transition begins, mobilized Libyans as well as other international actors, namely Russia and Turkey.

“[I]t created a false equivalence between the civilian leader of the country and the commander of one of the country’s multitude of armed groups.”

Russia has long used Libya’s slow-burning conflict to advance its relationships with Egypt and the UAE, while simultaneously expanding its influence on Europe’s southern border and its access to Libya’s natural resources. Sensing an international vacuum and an opportunity to leverage its influence in a petroleum-rich country in the southern Mediterranean, Russia pulled a page from its Syria playbook to prop up a weak and isolated authoritarian leader in a conflict most global actors wanted to avoid.

13 In September of 2019, Russia began to deploy an estimated 800-1,200 Russian mercenaries through the Wagner Group led by Yevgeny Prighozin, the same outfit that Russia has deployed to conflicts in Ukraine, the Central Africa Republic, Mozambique, and Mali. The Russian deployment tilted the balance of the conflict in Haftar’s favor.

14 Destabilization and conflict in Libya created opportunities for mischief, growing Russian influence in the region, and ensuring Russia played a role in any settlement.

Turkey has long maintained an interest in Libya as an economic partner where it holds over $20 billion in frozen contracts that, if resumed, might boost its otherwise worsening economy. Moreover, the success of the Haftar project would cement Emirati and Egyptian influence in North Africa and present a serious obstacle to Turkish prospects in the region.

Haftar’s assault on Tripoli forced Turkey to either move against or acquiesce to the UAE/Egyptian/Russian gambit to claim Libya. It also provided Turkey an opening to advance its eastern Mediterranean interests. Following the February 2018 discovery of significant gas reserves in the eastern Mediterranean, a coalition between Greece, Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt began to develop security and economic infrastructure, which Turkey viewed as a direct threat to its economic interests and dominant security role in the region.

15 The desperation of Libya’s GNA and the apathy of the West toward stopping Haftar gave Turkey the leverage it needed. By the end of November 2019, the besieged GNA readily signed an agreement that delineated maritime borders between Libya and Turkey and created an exclusive economic zone covering key gas fields in exchange for Turkish military support. With Turkish troops deployed and air support in place, the GNA was able to reclaim several strategic towns in western Libya in April 2020. Haftar’s forces have subsequently been forced to retreat to rear bases around Tripoli such as the town of Tarhouna.

A burnt-out vehicle left behind after a battle in Tripoli, April 2019. (Photo:

VOA)

The sudden and sharp growth of Turkish and Russian involvement since late 2019 has been happily absorbed by Libyan actors who are desperate not to lose. The military prowess of both countries has quickly led to them being key actors on the ground while impinging on European interests and potentially shutting the West out of any peace settlement.

The temporary truce declared on January 12, 2020, during a meeting in Moscow, highlighted these fears. The rapid announcement of the Berlin conference set for January 19, following months of high-level meetings, was Europe’s attempt to maintain relevance. At the end of March 2020, Europe launched a revamped naval operation, IRINI (Greek for “Peace”), to enforce the UN arms embargo in place since 2011. The formalization of Operation IRINI, however, has laid bare divisions within the European Union (EU) as Greece pushed for the mission to focus on disrupting Turkey’s naval resupply routes with the presumably larger aim of killing the Turkish-Libyan maritime and security agreement. In addition, enforcing a maritime arms embargo without a simultaneous blockade of arms coming overland from the UAE would, in effect, help Haftar. This calculation no doubt factored into Turkey’s decision to take matters into its own hands. It remains to be seen whether the EU, through the likes of Germany, will be able to use Operation IRINI to facilitate holding all embargo violators accountable, or if European divisions will ultimately cause the operation to be ineffective.

Escalation Ahead on the Eastern Front

“[U]nless nonaligned states can protect and support the UN to launch a genuine political process, the external actors engaged in Libya’s civil war will continue escalating.”

The war in Libya is set for a dramatic escalation. Given Haftar’s disadvantages in western Libya and the considerable Turkish support therein, Haftar is unlikely to make further gains and is already growing increasingly reliant on artillery just to maintain his positions. As the situation in western Libya worsens for him, he is likely to refocus his remaining offensive capacity on the de facto eastern front between the cities of Misrata and Sirte. However, further east, where Turkish air defenses are not present, he will likely remain unbreachable and comfortably absorb attacks by a GNA that is desperate to regain the country’s oil terminals.

As the war drags on, Europe has become more anxious at the potential destabilizing consequences of an internationalized conflict in its immediate backyard, potentially precipitating a new surge of refugees.

16 The active role of France, however, blunts the multilateral instruments—the EU and UN—that Europeans are most comfortable using. Meanwhile, the United States, which Europe is accustomed to depending on for any force projection, appears unwilling to engage in another intractable conflict, let alone one where allies such as the UAE and Turkey are in direct opposition.

It is almost inevitable that the UAE will seek to regain the upper hand through further deployments of mercenaries and weapons shipments. More crucially will be its attempts to regain aerial superiority from Turkey, which could involve importing Israeli air defenses following the inability of Russia’s Pantsir system to effectively neutralize Turkey’s drones.

17 Further severe losses could lead to the introduction of advanced Emirati and Egyptian aircraft. This would be a dangerous escalation that Turkey already seems to be preparing for with training drills involving its own F-16s in the Mediterranean.

All these developments point to an escalation of the increasingly destructive conflict. The removal of Haftar from western Libya may begin a new and perhaps more difficult campaign to dislodge the LNA from Libya’s oil fields in the south and oil terminals along its eastern coastline. More worrying for Libya’s future would be if Haftar moves to deepen the partition of the country in response to his military weakness. This could be done by trying to once again sell oil illicitly if he believes there will be no international pushback this time around.

Unless nonaligned states can protect and support the UN to launch a genuine political process, the external actors engaged in Libya’s civil war will continue escalating their attempts to seize control of this desert country that promises much yet delivers little more than squandered resources and frustration to its would-be overseers.

Supporting the UN and Avoiding Protracted Conflict

At its core, Libya’s war has been driven by the aspirations of regional powers, following their hijacking of the Libyan transition. These actors are now vying to reshape the region in their own image in a dangerous race to the bottom. Following are priority areas for policy action to reverse this trend and avoid an extended conflict in Libya.

Recognize the UN as the best honest broker. The escalation of the conflict by external actors means there are more interests and reputations at stake than there were previously. Given the relatively low costs each of these actors is incurring by supporting proxies, they have the means and incentives to continue escalation. By recognizing the UN as the best body to facilitate a de-escalation and negotiated settlement, all sides will have greater assurances that their interests will be considered. This reduces the “winner-take-all” undercurrent that has been driving the geostrategic aspects of this conflict. It is also the only option whereby Libyans will have the opportunity to reassert their sovereignty rather than existing as a vassal state to other regional actors.

Stop treating Haftar as a viable alternative. The impossibility of Haftar winning this war and being capable of ruling Libya has been made painfully clear with the GNA’s April 2020 offensives led by Turkey. Even before that, the scale of the mobilization triggered against him, his lack of a strong domestic constituency, absence of legitimacy, and his reliance on foreign mercenaries, equipment, and aircraft indicates that Haftar’s best case scenario would be a prolonged urban war that would destroy Tripoli and only set him up for further conflicts in cities like Misrata.

Having scuttled previous efforts by the UN and then launching an assault on the capital after agreeing to a power-sharing deal with Sarraj in February 2019, Haftar has proven himself an unreliable negotiating partner. Moreover, he has made his ambition to be Libya’s next authoritarian leader abundantly clear on multiple occasions and violated every ceasefire offered, including the terms of the January 2020 Berlin Conference.

Haftar, accordingly, seems to be the ultimate spoiler to de-escalation and stabilization in Libya. While Haftar is often treated as an essential part of a solution, in fact, a resolution to the conflict would be far easier by not treating him as the governing equivalent of the GNA. Better prospects can be realized by engaging those under him in order to enforce a ceasefire and build a joint security institution.

Display a unified European policy for the conflict in Libya. The lack of a unified European position on Libya has enabled Russia to gain leverage and expand its influence on Europe’s southern flank. This poses a far more serious threat to Europe than any intra-European differences. Russia’s deepening involvement in Libya, accordingly, should be a rallying point for EU and NATO members.

This does not necessitate partisan involvement in Libya’s war, but rather a common policy position from the West that enforces the UN arms embargo, defends international norms, upholds the integrity of Libya’s National Oil Corporation as the sole legitimate seller of Libyan oil, and ring-fences the UN process as the only game in town. This would significantly constrain Russia’s operation enacted through mercenary groups, arms transfers, and attempts to help Haftar sell oil illicitly. Not only would this make Russia’s involvement more costly for Moscow but it could also block further Russian expansion and counter the inroads Russia has already made.

Enforce international norms to stop the escalations. The violations of the UN Security Council-mandated arms embargo on Libya are a central driver of the conflict and allow Libyan belligerents, especially Haftar, to ignore calls for a ceasefire with impunity. Using assets such as the EU’s Operation IRINI as well as other satellite and aerial monitoring is a quick way to gather evidence on all violations that can be used to enforce the arms embargo in an unbiased fashion. If trying to hold violating states, such as the UAE, accountable is considered too politically sensitive, or if the Security Council is too divided to act, then other options remain available. A clear message can still be sent through unilateral sanctions on the private companies used by the UAE and others to send arms. Additionally, those who run private military contractors such as Yevgeny Prigozhin’s Wagner Group could also be sanctioned in an attempt to create an environment in Libya that is more conducive to peace.

A pressure campaign of this sort can also be applied to Libyan belligerents who seek to undermine the UN process. Similar sanctions in 2014 against the heads of rival parliaments and governments were considered key to facilitating the talks that birthed the Libyan Politic al Agreement and the GNA. Libyan actors and external governments that are attempting to undercut the UN process persist in doing so because they bear little cost to themselves. Moving to end this culture of impunity would be a relatively peaceful way of altering behaviors.

Make a national ceasefire more resilient through local ceasefires. The decentralized nature of Libyan society and the various militias that comprise both rival coalitions means that a national ceasefire can only be made resilient by engaging the communities actually fighting. Focusing on “local ceasefires” between directly warring communities such as Misrata and Tarhouna is a key step toward preventing the reemergence of conflict and starting to construct truly national security institutions in Libya. Working from the local level up is vital to alleviating the insecurities of communities that otherwise create openings for nefarious foreign involvement and building resilient institutions that can better resist foreign influence.

Tarek Megerisi is a policy fellow with the North Africa and Middle East program at the European Council on Foreign Relations, specializing in politics, governance, and development in the Arab world. He has worked extensively on Libya’s transition since 2012 with Libyan and international organizations.

Notes