(aggiornato alle ore 14 del 18 maggio)

Il generale (feldmaresciallo) Khalifa Haftar ha subito sconfitte militari brucianti sul fronte occidentale della Tripolitania e ha perso terreno sugli altri fronti mentre sul piano politico cerca di pararsi le spalle in Cirenaica con una sorta di “golpe” che mira a impedire al parlamento di Tobruk di estrometterlo per aprire negoziati con Tripoli.

E’ forse presto per dire se i recenti sviluppi potranno risultare decisivi nella lunga e complessa crisi libica ma certo stanno modificando la situazione di stallo determinatasi nell’ultimo anno, da quando prese il via l’offensiva dell’Esercito nazionale libico (LNA) di Haftar contro Tripoli.

Lo scontro per il controllo dei cieli

L’intervento militare turco su vasta scala con mezzi, droni, navi da guerra e migliaia di mercenari reclutati in Siria ha permesso alle forze del Governo di accordo nazionale (GNA) di conquistare tutto il territorio costiero tra Tripoli e il confine tunisino e le forze di Haftar sembrano sul punto di perdere anche la base aerea di al-Watiya, ultimo baluardo dell’LNA in quella regione, che resiste da settimane all’assedio e ai raid aerei dei droni turchi Bayraktar TB2.

Nelle ultime ore il GNA ha reso noto un video che mostrerebbe il lancio di un missile da un drone turco contro uno shelter corazzato nel quale si suppone fosse nascosto un sistema di difesa aerea Pantsir S1 fornito dagli Emirati Arabi Uniti all’LNA.

Il comando delle forze di Haftar a Bengasi ha invece annunciato ieri era che un analogo sistema antiaereo avrebbe abbattuto (nella foto d’apertura) ieri un drone turco,

probabilmente un TAI Anka, mentre sorvolava la base aerea di al-Watiya, 140 chilometri a sud di Tripoli e a 30 chilometri dal confine tunisino. Benchè parzialmente distrutto dagli scontri e soprattutto dai bombardamenti del GNA dell’ultimo mese, l’aeroporto ha un valore strategico per entrambi i contendenti.

La mattina del 18 maggio il GNA ha annunciato di aver occupato la base aerea di al-Watiya. “Il generale Osama al-Juwaili, capo della Sala operazioni congiunte ha reso noto che le nostre forze eroiche hanno preso il controllo della base aerea di al-Watiya” si legge sull’account Facebook dell’ Operazione “Vulcano di rabbia”.

La notizia è stata confernata dallo stesso capo del governo di Tripoli, Fayez al-Sarraj.

Il possesso della base aerea avrebbe permesso all’LNA di riprendere in futuro l’offensiva nell’ovest della Tripolitania; la sua conquista invece consentirà al GNA di cancellare la presenza nemica in quella regione mentre secondo alcune indiscrezioni alla base sarebbe interessata l’Aeronautica Turca che vorrebbe rischierarvi alcuni caccia F-16C per affiancare i droni Bayraktar oggi impiegati da Mitiga, Misurata e da altre piccole piste d’aviazione nei dintorni di Tripoli.

La presenza degli F-16C turchi nei cieli libici è già stata segnalata da alcune fonti d’intelligence ma sarebbe sporadica per la necessità di far decollare i caccia dalla Turchia rifornendoli in volo sul Mediterraneo con le aerocisterne KC-135. Oltre a questi velivoli la Turchia impiega sulla Libia anche aerei cargo C-130 e aerei radar Boeing E-7T oltre ai velivoli teleguidati Anka e Bayraktar.

Un’iniziativa che rappresenterebbe la risposta di Ankara al recente rischieramento in appoggio all’LNA di almeno 6 Mirage 2000 emiratini nella base aerea di Sidi el-Barrani, nell’Egitto occidentale non lontano dal confine libico, svelati da alcune foto satellitari (qui sotto).

L’obiettivo di Abu Dhabi, che già da tempo schiera nella base di al-Khadim, non lontano da Bengasi, elicotteri, droni Wing Loong 2 e aerei antiguerriglia AT-802U a supporto dell’LNA, è bilanciare la superiorità nei cieli acquisita negli ultimi mesi dal GNA grazie all’intervento della Turchia che sembra aver pagato il successo con la perdita di

almeno 32 droni in turco dal novembre 2019.

Inoltre l’LNA ha reso noto nei giorni scorsi di aver ripristinato l’efficienza operativa di 4 cacciabombardieri già in servizio (ereditati dalle forze aeree di Gheddafi) senza però precisare se si tratti di Mig 21, Mig 23 o Mirage F-1

Non è la prima volta che F-16C egiziani e Mirage 2000 egiziani o emiratini vengono segnalati in azione nei cieli libici in appoggio alle truppe di Haftar ma le ultime segnalazioni potrebbero indicare un’escalation del conflitto aereo che un ruolo diretto e continuativo dei caccia dei paesi che supportano direttamente le due fazioni libiche: di fatto la manifesta internazionalizzazione del conflitto.

Rinforzi per tutti

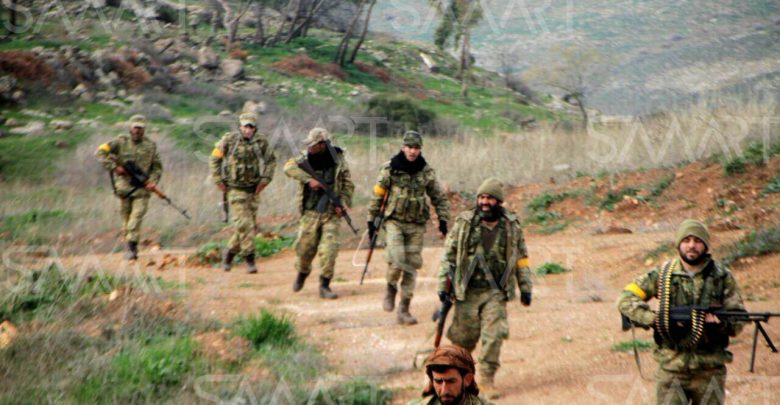

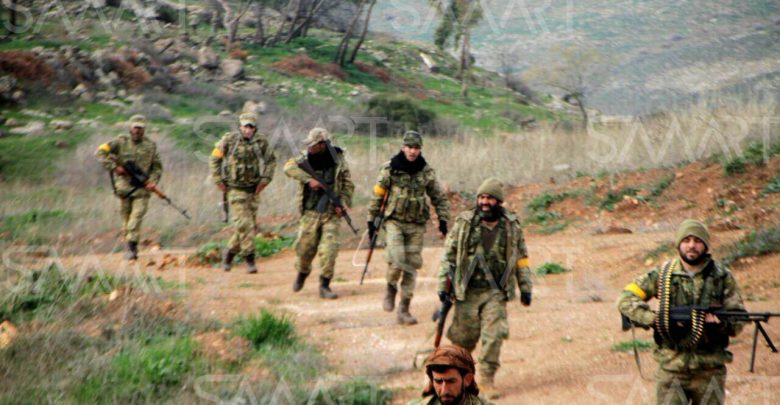

Uno sviluppo che rappresenta una conseguenza diretta delle sconfitte di Haftar a ovest di Tripoli e dell’arresto della sua offensiva a sud della capitale e a est di Misurata, determinate direttamente dall’intervento di militari turchi (stimati tra 500 e mille unità) e

dei mercenari siriani arruolati da Ankara il cui numero era valutato a marzo in circa 5mila (a cui sottrarre almeno 500 tra morti, feriti e prigionieri) ma che secondo sarebbe salito attualmente a quasi 8mila unità, a conferma della volontà turca di aiutare il GNA a respingere il nemico lontano da Tripoli e, lungo la costa a est di Misurata, di ricacciarlo a Sirte.

Il 6 maggio l’Osservatorio per i diritti umani in Siria (Ondus, con sede a Londra), ha reso noto che negli ultimi mesi il governo di Ankara ha inviato in Libia 7.850 miliziani, siriani e di nazionalità non precisate, mentre ha radunato nei centri di addestramento in Turchia circa altri 3mila combattenti. L’Ondus ha aggiunto che a quella data si registravano 261 mercenari siriani uccisi in battaglia in Libia.

Tali forze sarebbero concentrate al momento soprattutto a Tripoli e Garabulli per sostenere l’offensiva verso Tarhuna, 70 chilometri a sud di Tripoli dove le forze dell’LNA hanno il loro comando e resistono da settimane alla pressione nemica sostenuta dal cielo dai droni turchi che avrebbero distrutto al suolo nelle ultime settimane almeno due cargo dell’LNA, un Iliyushin Il-76 e un Antonov An-26 che per rifornire la città utilizzano la striscia d’asfalto della strada per Tripoli.

Al netto delle dichiarazioni dei contendenti la situazione su questo fronte è molto vivace ma non sembra indicare svolte decisive anche se la caduta di al-Watya nell’ovest potrebbe consentire al GNA di concentrare maggiori forze intorno a Tarhuna.

L’LNA resiste intorno a Tarhuna e non lesina contrattacchi verso Garabulli il cui possesso permetterebbe alle forze di Haftar di tagliare la strada costiera impedendo i collegamenti tra Tripoli e Misurata.

Al tempo stesso l’LNA ha accentuato i bombardamenti con razzi d’artiglieria su Tripoli, in particolare sull’aeroporto di Mitiga impiegato dai velivoli cargo e dai droni turchi, sul porto e sulle aree adiacenti e ambasciate di Italia e Turchia, i principali sostenitori del GNA. Bombardamenti che hanno indotto Ankara a minacciare Haftar di rappresaglie militari contro la Cirenaica.

I droni Wing Loong 2 dell’LNA (ma gestiti da contractors al solo degli Emirati Arabi Uniti) hanno bombardato anche il comando delle forze del GNA a Zuara, a ovest di Tripoli e le postazioni nemiche a Gharyan, ex caposaldo dell’LNA a sud della capitale, riconquistato dal GNA l’anno scorso.

A causa della superiorità aerea del GNA, Haftar ha difficoltà a rifornire le truppe a sud di Tripoli e le incursioni dei droni turchi hanno colpito nelle ultime settimane diversi convogli che da Bani Walid puntavano a raggiungere Tarhuna dove il comando dell’LNA inquadra anche contractors russi e militari emiratini e giordani.

Anche sul fronte di Misurata l’LNA è stato costretto a ripiegare verso est, tra Abu Grein e Sirte.

Le difficoltà dell’LNA stanno inoltre incoraggiando alcune tribù a cessare il sostegno ad Haftar e a schierarsi col GNA come hanno fatto ad ovest le milizie berbere della regione del Nefusa e come sembra stia accadendo anche nell’area di Murzuq, a sud di Sebha, nel profondo meridione libico, dove i Tebu mobilitano le milizie e rifiutano di accettare il dominio di Haftar.

Haftar punta al controllo politico

Le sconfitte e le incertezze militari hanno determinato un approccio critico nei confronti del generale da parte dei suoi principali sponsor militari (Egitto, Russia ed Emirati Arabi Uniti) e maggiori aperture all’iniziativa di Aguilah Saleh, autorevole presidente del parlamento di Tobruk considerato vicino a russi e sauditi che vorrebbe un negoziato di pace con Tripoli.

Per scongiurare tale iniziativa, che potrebbe di fatto esautorarlo, il 27 aprile Haftar ha annunciato una sorta di golpe in Cirenaica dichiarando di accettare un fantomatico “mandato popolare” a governare tutta la Libia indicato da alcune manifestazioni di piazza di suoi fedelissimi.

Il generale ha annunciato in televisione di avere un “mandato per svolgere un compito storico” per “occuparsi del Paese”, attribuendosi pieni poteri per governare la Libia, in realtà solo i territori sotto il controllo delle sue forze.

Haftar ha quindi denunciato l’accordo di Skhirat col quale l’ONU diede vita al governo di Fayez al-Sarraj a Tripoli pur riconoscendo la legittimità del parlamento di Tobruk, fino a ieri vicino ad Haftar.

Con l’aiuto dei militari Haftar sta costituendo il Consiglio di sovranità libico, di fatto un governo i cui ministri saranno per lo più generali che esautorerà l’esecutivo della Cirenaica guidato da Abdullah al-Thani e terrà sotto scacco il parlamento di Tobruk, col compito di mettere a punto nuove elezioni presidenziali e parlamentari che sarebbero ovviamente pilotate da Haftar ed effettuate solo nelle regioni sotto il suo controllo.

Il 16 maggio un gruppo di deputati del parlamento di Tobruk ha condannato l’arresto da parte degli uomini di Haftar del ministro del Tesoro del governo della Cirenaica, Kamel al Hasi, considerato vicino alle posizioni favorevoli al negoziato con Tripoli di Aguila Salehg. In una nota una decina di deputati definiscono l’arresto del ministro “illegale” e ne chiedono l’immediata scarcerazione.

Il “golpe” militare del generale, almeno ufficialmente, ha riscosso critiche e scetticismo anche tra i paesi alleati di Haftar anche se, come spesso accade, nella crisi libica il gioco delle parti è prassi comune e molti Stati hanno agito in passato in aperta contraddizione con quanto dichiarato. Tutti a parole si dicono a favore di negoziati di pace ma ognuno sostiene con armi e denaro la propria fazione.

La forza di Haftar, che a 76 anni e in un momento di complessiva debolezza militare non intende rinunciare al ruolo di protagonista, è riposta nella consapevolezza dei paesi arabi che le sue milizie costituiscono l’unico strumento con cui ostacolare la massiccia penetrazione turca (e del Qatar) in Libia.

Un’operazione finanziata probabilmente dagli Emirati Arabi Uniti, oggi partner di Bashar Assad, che viene interpretata come un rafforzamento della penetrazione russa in Libia, dove già operano contractors della società militare privata Wagner stimati tra 800 e 1.200 unità da un rapporto confidenziale della missione dell’ONU in Libia rivelato

dall’agenzia di stampa Reuters il 7 maggio.

L’irritazione di USA e NATO

Il ruolo russo in Libia e l’invio di combattenti siriani a rinforzo dell’LNA, denunciato anche dall’inviato speciale di Washington per la crisi siriana, Jim Jeffreys, sta irritando Stati Uniti e influenzando, di conseguenza, i vertici della NATO che però erano rimasti quasi impassibili di fronte allo sbarco a Tripoli di migliaia di miliziani jihadisti siriani arruolati da Ankara.

Iniziative che stanno favorendo da un lato il ricompattamento tra l’Alleanza Atlantica e la Turchia e dall’altro più stretti rapporti tra il GNA e gli USA.

Il premier di Tripoli, Fayez al Sarraj (nella foto a lato con il presidente turco Erdogan), ha avuto il 15 maggio un colloquio telefonico con il segretario generale della NATO, Jens Stoltenberg, che ha confermato che il GNA è il governo legittimo della Libia ed ha aggiunto che i raid che colpiscono i civili “non sono tollerabili”, ribadendo che “non c’è soluzione militare per la crisi libica e che è necessario attenersi alle conclusioni della conferenza di Berlino”.

Lo stesso giorno Stoltenberg ha avuto un colloquio telefonico anche con il presidente turco Recep Tayyip Erdogan, ribadendo (lo riporta una nota di Ankara) la disponibilità della Nato ad aiutare il governo di Tripoli ad aumentare le proprie capacità securitarie e di difesa nel pieno sostegno a una soluzione politica alla crisi.

Nei giorni precedenti Henry Wooster, vice segretario aggiunto dell’Ufficio degli affari del Medio Oriente del Dipartimento di Stato aveva dichiarato che “gli Stati Uniti non sostengono l’azione dell’LNA contro Tripoli. L’attacco alla capitale devia le risorse da quella che è una priorità per noi, ovvero l’antiterrorismo”.

L’Operazione Irini e la sfida energetica

Resta invece critica la valutazione del GNA nei confronti dell’Unione Europea dell’operazione navale Irini che dovrebbe contrastare le forniture di armi ai contendenti libici ma che di fatto ha le potenzialità per mettere in difficoltà solo i convogli navali turchi diretti a Tripoli e Misurata.

Il 4 maggio il vice del GNA, Ahmed Maitig (nella foto a lato ), ha affermato che l’Operazione Irini “non è sufficiente e trascura il monitoraggio delle frontiere aeree, marittime e terrestri orientali della Libia. L’Unione europea non ha consultato il nostro governo prima di prendere la decisione di avviare l’operazione che si affaccia sui confini orientali”, ha aggiunto Maitig durante un incontro con l’ambasciatore d’Italia a Tripoli, Giuseppe Buccino.

Al-Sarraj, in un’intervista al Corriere della Sera ha rincarato la dose dichiarando che la nuova missione europea ha “come obiettivo primario quello di fare rispettare l’embargo Onu contro l’invio di aiuti militari stranieri in Libia.

La sua area d’operazioni è il mare Mediterraneo ma ai nostri nemici armi e munizioni arrivano principalmente via terra e aria. I nostri porti saranno controllati, le nostre truppe penalizzate, mentre gli scali di Haftar saranno liberi di ricevere ogni aiuto e le sue milizie di utilizzare qualsiasi tipo di rinforzo militare”.

Superficiale e poco concreta la risposta giunta dal portavoce della Commissione Ue, Peter Stano. “Posso solo dire che Irini è un concreto esempio di come l’Ue voglia contribuire alla pace in Libia. Il suo mandato mira a contribuire al rispetto dell’embargo dell’Onu così da prevenire il flusso di armi verso la Libia e di partecipare al raggiungimento di una soluzione politica”.

Da un lato Irini non sembra avere molto supporto dagli stessi Stati Ue. è in mare con una sola nave, la fregata francese Jean Bart (nella foto a lato), che verrà però riturata a fine mese quando entreranno in azione una nave per operazioni anfibie (LPD) italiana e una fregata greca: navi che solo in estate potrebbero venire affiancate da una nave tedesca, probabilmente un rifornitore di squadra.

La ragione

dell’avvio lento e poco convincente dell’operazione navale Ue a comando italiano sembra legato a due aspetti: i greci interpretano la missione come una iniziativa anti-turca mentre molti partner del nord Europa non hanno intenzione di farsi coinvolgere in un’iniziativa che potrebbe portarli ai ferri corti con Ankara.

La Turchia, che la considera illegittima, rileva come non casuale il fatto che l’area operativa dell’Operazione Irini sia situata di fronte alle coste della Cirenaica, in quello specchio di mare che in base

all’accordo bilaterale del 29 novembre 2019 appartiene alla Zona economica esclusiva (ZEE) Turchia e Tripoli intendono sfruttare congiuntamente.

Il 15 maggio la Turkish Petroleum Company (Tpao) ha chiesto al GNA il permesso di effettuare prospezioni petrolifere nel Mediterraneo orientale. “Le attività di prospezione inizieranno non appena il processo sarà completato”, ha dichiarato il ministro turco dell’Energia, Fatih Donmez, durante una conferenza stampa ad Ankara.

La dichiarazione è giunta dopo che i ministri degli Esteri di Grecia, Cipro, Egitto, Francia ed Emirati Arabi Uniti (in pratica tutti avversari di Ankara e sponsor del generale Haftar) hanno denunciato le “attività illegali turche in corso” nella ZEE di Cipro e nelle sue acque territoriali, nonché le “ingerenze” turche in Libia.

I cinque hanno ricordato “l’impegno ad astenersi da qualsiasi intervento militare straniero in Libia, come concordato nelle conclusioni della conferenza di Berlino e condannato “fermamente l’interferenza militare della Turchia in Libia” esortandola a “rispettare pienamente l’embargo sulle armi”.

Grecia, Cipro ed Egitto sono inoltre accomunati dalla condanna del memorandum d’intesa fra Ankara e Tripoli sulla delimitazione delle giurisdizioni marittime nel mar Mediterraneo, che a loro giudizio lede i loro diritti sovrani.

Giornalista bolognese, laureato in Storia Contemporanea, dal 1988 si occupa di analisi storico-strategiche, studio dei conflitti e reportage dai teatri di guerra. Dal febbraio 2000 dirige Analisi Difesa. Ha collaborato o collabora con quotidiani e settimanali, università e istituti di formazione militari ed è opinionista per reti TV e radiofoniche. Ha scritto diversi libri tra cui "Iraq Afghanistan, guerre di pace italiane" e “Immigrazione, la grande farsa umanitaria”. Dall’agosto 2018 al settembre 2019 ha ricoperto l’incarico di Consigliere per le politiche di sicurezza del ministro dell’Interno.